A new suspect named in a case that changed Britain

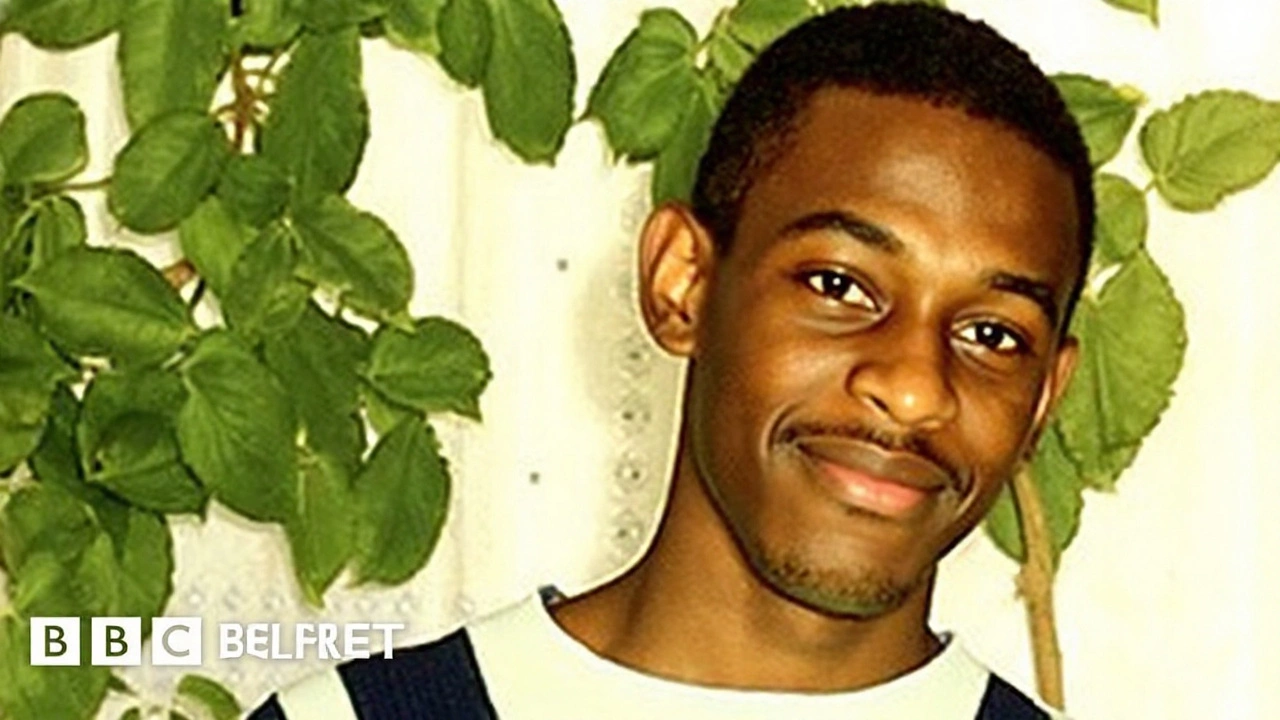

More than three decades after the killing that forced Britain to confront racism in its institutions, police have named a sixth suspect in the murder of Stephen Lawrence. The Metropolitan Police said Matthew White, long described in the case as “the fair‑haired man,” is now formally a suspect in the 1993 attack that left the 18‑year‑old student dying on a south London pavement.

White’s name has circled the investigation for years. Records show he was arrested in 2000 and again in 2013 but was never charged because detectives said they lacked evidence. The latest move comes after renewed scrutiny of investigative failures, including a stark detail: it took authorities 20 years to interview a key relative of White who held crucial information. That delay, another painful chapter in a case defined by missed chances, has now pushed the police to elevate White’s status to suspect.

The naming follows a major twist earlier this year. In March 2025, David Norris — one of two men convicted in 2012 — admitted for the first time that he took part in the attack and said he punched Lawrence. His admission doesn’t change his conviction, but it matters in two ways: it aligns with accounts that a group swarmed the teenager, and it may help unlock fresh testimony from people who have stayed silent for decades.

The College of Policing has opened a new investigation into the murder, adding weight to the Met’s appeal for information. Stephen’s mother, Doreen Lawrence, whose relentless campaign exposed institutional failings, has urged anyone with knowledge of the attack — even fragments — to step forward. Police still want to identify a man captured in an enhanced CCTV image released in 2016, believed to be a witness who has never been traced.

Lawrence was attacked on 22 April 1993 in Eltham, southeast London, while waiting for a bus with a friend. The assault was swift and unprovoked, and it was racial hate that drove it. The brutality of the stabbing, the speed with which the attackers fled, and the poor early response from police all fed a sense that justice might never come.

The public pressure that followed was unlike anything Britain had seen in a murder inquiry. Years of marches, court battles, and media investigations forced the state to look hard at itself. The 1999 Macpherson Report — launched after the original inquiry faltered — concluded the Metropolitan Police was “institutionally racist.” It catalogued failures in the first investigation, from poor scene preservation and missed forensic chances to the undervaluing of witness accounts and the family’s voice.

Change did come, slowly. A legal shift in 2003 allowed suspects to be retried for serious crimes if new and compelling evidence emerged, ending the old “double jeopardy” bar for cases like this. A cold case review that began in 2006 used advances in forensics to find what had been missed: a microscopic blood stain from Lawrence in Gary Dobson’s jacket and fibers from Lawrence’s clothing on items linked to both Dobson and Norris. Those findings were pivotal.

In 2012, the Old Bailey convicted Dobson and Norris of murder. They were given life sentences, with minimum terms set by the judge. They remain in prison, though they are now within the window to apply for parole. For the Lawrence family, those convictions marked real progress, but not closure. Three other original suspects — part of a group long named in public — have never faced a jury for the killing.

White’s emergence as a formally named suspect adds pressure to a cold case that never truly went cold. The unanswered questions are stark. Why did it take two decades to interview a relative whose evidence could have shifted the investigation sooner? How many leads went unexplored as the case passed from team to team? Police say they are reviewing where decisions went wrong and whether new lines of inquiry can now be pursued.

The Met’s announcement also brings the investigation back to the public. Detectives are appealing to anyone who knew White in the early 1990s, anyone who heard confessions or boasts, and anyone who might place him with the known group on the night of the attack. The message is blunt: loyalties that held in the 1990s may not hold now, and tiny details can move a historic case forward.

Forensic science remains a key hope. Advances that helped secure the 2012 convictions came from microscopic traces that were invisible to earlier methods. Modern techniques can re‑examine old items for transferred fibers, touched DNA, and environmental traces that weren’t detectable even a decade ago. The challenge is preservation: items must have been kept properly, and contamination risks must be addressed in court.

Yet the case has never been only about evidence bags and lab reports. It is about trust — the trust a grieving family places in a system to do its job. Doreen Lawrence’s campaign reshaped British policing culture. Family liaison protocols were overhauled. Stop‑and‑search data had to be recorded more carefully. Hate crime recording improved. Forces were pushed to reflect the communities they serve and to confront bias, not just deny it. Those changes are part of Stephen’s legacy.

The new suspect naming also comes as campaigners warn against fatigue. Each anniversary brings statements and pledges; what moves the dial are witness accounts, credible new forensic results, and hard decisions by prosecutors. David Norris’s recent admission could break a long‑standing code of silence. If one attacker admits presence and assault, investigators hope others may either corroborate or seek to distance themselves, opening the door to usable testimony.

So what might happen next? If investigators gather fresh, reliable evidence against White or any other suspect — whether scientific, witness, or both — prosecutors could consider charges. With historical cases, the standard is the same: a realistic prospect of conviction and the public interest test. Courts also examine whether delays have made a fair trial impossible. That is one reason investigators emphasize corroboration and clarity: memories fade, but science and documented timelines can anchor a case.

Lawrence’s story is now part of Britain’s story. Schools mark Stephen Lawrence Day on 22 April, an annual reminder of what was lost and what must change. Scholarships and community programs carry his name. The family’s foundation supports young people from under‑represented backgrounds — a nod to Stephen’s ambition to become an architect and to the doors he never got to walk through.

For those new to the case, the key names matter because the history is complicated. The original group commonly linked to the attack included Gary Dobson, David Norris, and three others frequently named in public debate. Only two were convicted. The three who have never been convicted for the murder remain outside a courtroom’s judgment, even as their names have become part of a national reckoning with race, class, and power.

There is also a lesson about persistence. The 2006 cold case review didn’t discover the truth in one sweep; it built it grain by grain. A single microscopic blood spot led to a conviction. Fibers no wider than a hair mapped contact between victim and suspects. Cases like this turn on patience, not a single breakthrough. That is why investigators keep returning to stored evidence, old statements, and overlooked witnesses.

The renewed focus on Matthew White underlines how much work remains. Police want to hear from anyone who knew him in the early 1990s — friends, neighbors, people from pubs and bus stops in Eltham and nearby areas. They also want to speak to the person in the 2016 enhanced CCTV image, believed to have been near the scene. Even a small detail — a route taken, a jacket worn, a remark remembered — can help build a timeline that holds up in court.

The Metropolitan Police, under pressure from Parliament and the public, has promised transparency about the past missteps: why leads weren’t followed, how handovers between teams lost momentum, and which decisions delayed action on White. The fact that a key relative wasn’t interviewed for 20 years is now a case study in what can go wrong when investigators don’t cast the net widely and early.

For the Lawrence family, time has never softened the mission. They fought for the Macpherson inquiry, for changes to double jeopardy rules, and for forensic reviews that proved decisive. The new investigation by the College of Policing and the Met’s public appeal show the case is not parked on a shelf. It is active. Whether it delivers more charges will depend on what surfaces now.

Key moments and why they matter

- 22 April 1993: Stephen Lawrence is killed in a racist attack while waiting for a bus in Eltham, southeast London.

- 1999: The Macpherson Report concludes the Metropolitan Police is “institutionally racist” and sets out sweeping reforms.

- 2003: The law on double jeopardy is changed, allowing retrials for serious crimes when new evidence emerges.

- 2006: A cold case review begins, using advanced forensic techniques to re‑examine clothing and trace evidence.

- 2012: Gary Dobson and David Norris are convicted of murder after new blood and fiber evidence is presented.

- 2016: Police release an enhanced CCTV image of a potential witness they have yet to identify.

- 2025: David Norris admits his role, saying he punched Lawrence during the attack; police name Matthew White as a sixth suspect.

The case still asks hard questions of British policing: how to handle community trust, how to manage complex historic inquiries, and how to avoid the failings that defined the first investigation. It also asks something simpler of the public: if you know something, say it now. Silence protected killers in 1993. It does not have to protect them in 2025.